|

Fall 2021

WHRC COMMITTEE & STAFF

Chairman: Hope Royer

Committee Members: Mary Baird, Carolyn Forbes

International President: Marian St.Clair

Our Home, 1734 N Street

By Hope Royer, WHRC Committee Chairman

Emile-Louis Picault’s bronzed statue Le Génie Humain, ca. 1900, is posted mid-way up the grand staircase to the formal rooms on the second floor of 1734 N Street NW. The Art Nouveau statue allegorizes the human quest for knowledge. Le Génie Humain shows a winged young man with one arm outstretched. His hand rests on a manuscript. The Latin words “Ad Ignotum,” or “toward the unknown,” are inscribed on the manuscript. It seems fitting that the angel perched in the majestic hallway would be laden with knowledge, looking up toward the light, symbolic of the clubwomen whom it guides.

The Music Room to the right at the top of the grand stairway was created in 1926 with the addition of a Jonas Chickering baby grand piano and bench, ca. 1925. GFWC International Past President Mary Belle King Sherman (1924-1928) purchased the piano to be placed at Headquarters. She believed that a house could not be a true home without the addition of music.

The Woman’s Club

By Hope Royer, WHRC Committee Chairman

Following the formal opening of Headquarters in January 1923, individual clubwomen and State Federations began to donate fine furniture, art work, silverware, and books to help create a more “home-like” environment.

Women, their fashions, and their interests were of public interest and magazine articles often profiled the “clubwoman” or “the woman’s club.” In 1927, McCall’s magazine published a painting entitled The Woman’s Club by David Robinson that portrayed a variety of faces and attitudes in an audience of woman’s club members. The painting was used to illustrate a Dorothy Canfield article about “3, 000,000 women.” The painting attracted much attention when it was exhibited in Nebraska in 1927. Nebraska Federation members requested the painting be presented to GFWC Headquarters and the artist contributed it in honor of the first Nebraska state president, Flavia Camp Canfield. The formal presentation was made at the 1928 biennial convention in San Antonio, Texas.

GFWC Legacy Club

By Mary Baird, WHRC Committee Member

The idea for the GFWC Legacy Club came about at a GFWC North Carolina Convention, when Debby Bryant and Melanie Carriker had a conversation about their experiences as daughters of State Presidents. The idea continued to grow at the following Region Conference as others joined the discussion, including Mary Jo Thomas, Rosemary Thomas, and Babs Condon.

The concept was to form a club for those inspired to become a GFWC member because of their relationship with a grandmother, mother, aunt, sister, or other family member. The object of the club is to maintain the bonds of clubwomen who share GFWC membership through several generations of their families, to support the ideals and programs of GFWC, and to be a legacy of the Federation. The club charter was signed in 2015 by GFWC International Past President Babs Condon and her mother, GFWC Maryland Past State President Mrs. Barbara Peck, as well as GFWC North Carolina Past State President Wendy Carriker and her daughter, Melanie Carriker, and GFWC International Past President Juanita Bryant and her daughter, Debby Bryant. The first club president was Melanie Carriker.

Membership in the Legacy Club includes those who are first generation and beyond clubwomen. The club’s annual meeting is held during the GFWC Annual Convention. Current membership is approximately 60 members. The club has traditionally made a donation to the GFWC Women’s History and Resource Center. In 2020, the club celebrated the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment with a donation of $350 to the WHRC.

The club is open to any current clubwoman that has a legacy connection to GFWC through a family member. For more information on membership, contact one of the current club officers: President Rosemary Thomas, Vice President Susette Redwine, Secretary Dianne Maki-Sethi, or Treasurer Debra Bryant.

Madame Demorest, GFWC, and Fashion History

By Hope Royer, WHRC Committee Chairman

Ellen Louise Curtis was born in Schuylerville, New York, in 1824. After graduating from school at the age of 18, she moved to Saratoga Springs, New York, where she opened a millinery shop with financial help from her father, a hat factory owner. Ellen later moved to New York City with her business and in 1858 she married William Jennings Demorest, a dry goods merchant. In 1860, Madame Demorest and her husband began the home sewing pattern industry by holding fashion shows in their homes and selling the patterns. This was the beginning of the Mme. Demorest’s Emporium of Fashion. They published a magazine, Demorest’s Mirror of Fashion, which listed hundreds of different patterns, most available in only one size. The patterns of unprinted paper, cut to shape, could be purchased “flat” (folded), or, for an additional charge, “made up” (with separate pieces tacked into position).

Mme. Demorest’s paper patterns originated during a time of great social change when the sewing machine was becoming increasingly available and a growing middle class was clamoring for access to affordable fashion. The paper patterns reached women across America and Europe, providing them with up-to-date styles. Mme. Demorest claimed a number of innovative products, but her mass-produced and marketed paper dress patterns remain her most important contribution and were key in building one of the most important and influential fashion empires in the late 19th century.

Ellen Louise Curtis Demorest was a co-founder of Sorosis, the founding club of GFWC. Jane Cunningham Croly was the chief staff writer for her fashion magazine, Demorest’s Mirror of Fashion.

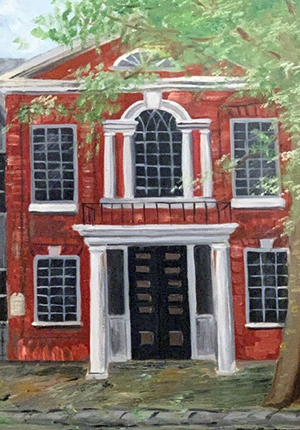

Preserving the Past: Clubhouse History of the Dover Century Club (GFWC Delaware)

By Carolyn Forbes, WHRC Committee Member

With appreciation to: Mary Lisa Carey, Jerry Travers, and Sandy Swaka-Farrow

Laid out in 1717, Dover Green followed a 1683 plan by William Penn that provided a gathering area for the growing town. The Green has played its part in history, from the American Revolution to the founding of our nation, women’s rights, civil rights, and beyond. Throughout the years, the now historic area grew as homes and businesses were established.

In time, Rev. John P. Thompson and workers who labored in the area were encouraged by an appeal to the Baptist House Society to organize a new church. They began raising funds in 1847 to purchase land facing Dover Green. The building’s cornerstone was set on September 9, 1850, and the church was officially established on January 8, 1852. More than 40 years later, the building became the headquarters of the Dover Century Club.

A group of women that later became the Dover Century Club had their very first meeting at the church in July 1897. In 1901, three years after its incorporation as the Dover Century Club, the club purchased the church from the Baptist House Society for $1,000. The purchase of the clubhouse gave the club a greater dignity and ensured it a permanent home on historic Dover Green. By 1907, the building was paid for, and in 1911 electricity was added.

The house features hardwood floors and tall ceilings on the second floor. It has four large windows and a large lead glass palladium window overlooking historic Dover Green. As the building is entered, two staircases, one to the left and one to the right, lead to the second floor. Straight ahead on the first floor is the Tea Room. The Dover Century Club is well known for its elaborate Afternoon Teas.

Throughout the years, the club has owned three pianos. The first piano was acquired just after the purchase of the clubhouse. The second, purchased in 1910, cost $350. In 1938, the Renn London Grand Piano was purchased at a cost of $262 and graces the platform to this day. A painting of lotus lilies, the club’s emblem, was created and presented by a club member, Miss Murphy, in the early years. The furniture on the platform was purchased from proceeds of luncheons to serve to the State Executive Board and cost $120.50.

In May 1920, a memorial tree was planted on the Dover Green in honor of the Dover boys in service during the First World War. In 1932, an organized movement for patriotic celebrations in the United States swept across the country and a tree was planted in front of the clubhouse with an elaborate service to honor the 200th anniversary of the birth of George Washington.

During the two World Wars, the Dover Century Club members gave their time and energy generously. Clubhouse use was freely extended for all patriotic meetings, including those held by the Red Cross and the USO, liberty loan drives and national clothing drives, and as a center for classes, meetings, and a depository for clothing.

In addition to hosting monthly membership meetings, executive committee meetings, workshops, and special events, the public is often welcomed to tour the club’s beautifully preserved building with its white columned entrance and magnificent palladium window. Visitors explore the Dover Century Club clubhouse and surrounding areas as part of walking tours and lantern tours, and as a part of historical and other programming conducted by the First State Heritage Park.

Members have taken great care of the building, both maintaining and improving the structure and interior. Its last major restoration, completed in 2015, was made possible by donations and a grant from the Longwood Foundation and the Dover Housing Authority. As a result, the club was awarded the 2016 James H. Jackson Historic Preservation Award from the Friends of Old Dover.

GFWC Delaware and the Dover Century Club will celebrate a 125 year anniversary in 2022. A gala celebration is being planned.

It’s All About Hats…

By Hope Royer, WHRC Committee Chairman

When the California Federation hosted the 1924 biennial convention in Los Angeles, Mrs. Augusta W. Urquhart was State Federation President. Like all State Federation presidents of that era, Mrs. Urquhart was often interviewed by the press and quoted on a variety of subjects. In her case, those subjects often included Americanism, prohibition, and law enforcement.

The popular Augusta Urquhart also attracted attention for her wardrobe during a time when hat styles had evolved from wide brims and plumes of egret feathers to less “ostentatious” creations. One writer, who claimed that “the higher a woman goes in club office, the greater the improvement in her choice of head gear,” wrote about the changes in Mrs. Urquhart’s hats, noting, “When first I knew Mrs. Urquhart, she wore hats of modest mien, clubby looking. Later, when she assumed the duties of district president, her hats immediately assumed a more distinctive and important air as was consistent with her office. Now that she is state president of the California Federation of Women’s Clubs, the change in her character is remarkable. Her chapeaus now are most superior looking, as they echo the wearer’s preeminence. At a recent luncheon, her pre-Easter creation was a stunning Gloria Swanson poke of the latest mode.”

Arts, Culture, and the Clubwoman

By Marian St.Clair, GFWC International President

The most noteworthy painting at our GFWC home in Washington, D.C., is Mt. McKinley National Park, by Sydney Laurence in 1923. Donated in the same year to the General Federation Headquarters by the Alaska Federation, it is also estimated to be the most valuable of the many art works in the GFWC collection.

Laurence painted Mt. McKinley, now known as Denali, many times and is best known for his images of the great mountain. In his long career, Laurence painted many scenes of the Alaska wilderness, from rocky coasts to rustic cabins. He also depicted the often solitary lives of natives and newcomers who fished, prospected, and trapped in the harshest conditions. More than any other artist, his paintings defined Alaska as “the last frontier.”

By the time Laurence completed Mt. McKinley National Park he had been acknowledged as Alaska’s most renowned painter. Born in Brooklyn in 1865, he studied at the Art Students League of New York before marrying and moving to England, where he settled in the English artists’ colony of St. Ives, Cornwall, in 1889. Throughout the next decade, Laurence exhibited at the Royal Society of British Artists and the Paris Salon. For unknown reasons, Laurence left his family in 1903 and traveled to Alaska, where he primarily lived until his death in 1940. More details about Laurence’s life are available in his online biography.

Stylistically, Laurence is known as an American romantic landscape painter. He utilized “tonal” techniques learned in New York and Europe to give a unique character to his art works, including those of Alaska. In brief, Tonalism is a style that creates an impression of mist or atmosphere over landscape forms that conveys a personal affinity for nature. Artists associated with this technique frequently used dark, natural hues such blue, brown, and gray.

Displayed in a place of honor over the fireplace mantel in the Music Room, Mt. McKinley National Park depicts the artist’s most important and well-known image in his characteristic style, which increases its importance and its value. With its original frame, the artwork is also monumental in size—measuring roughly five and a half feet tall by four and a half feet wide.

After GFWC purchased 1734 N Street NW in 1922, many of its furnishings and decorations were donated by GFWC State Federations. Information on the Laurence painting in GFWC archives does not provide an account of how it was transported from the artist’s studio in Anchorage, Alaska, to Washington, D.C., but that in itself must have been a feat. We can only imagine the pride of the Alaska Federation in bestowing such a gift and the thrill of President Alice Ames Winters in welcoming it to GFWC Headquarters.

It is interesting to note that many of the paintings donated to GFWC by clubwomen throughout the years portray their region, state, or community, so members and visitors see the geographic diversity of our Federation reflected on our walls.

While collecting art for Headquarters, GFWC also encouraged clubwomen to promote and collect art themselves, some of which was used to ornament schools, libraries, and other public buildings across the country. Within a decade, in 1930, GFWC adopted the Penny Art Fund to purchase various types of art and mount traveling exhibits that not only educated citizens, but also helped sustain artists during the Great Depression.

The collection arising from these efforts, most especially Mt. McKinley National Park, illustrate the significant role that art education and appreciation have played in GFWC’s history, while also providing a tangible and exciting connection to our past.” |